Globally, seafood consumption is at an all-time high, but consumers are often given little information about the origins of the food on their plate. Due the systematic lack of transparency within the seafood industry, seafood companies rarely disclose what or where they are fishing and consumers might not be eating the seafood they purchased. The recent increase in demand for seafood has resulted in the expansion of industrial fishing, which has led to the overexploitation of biodiversity in the high seas—the nearly 60% of the global ocean beyond national jurisdiction. Thirty-nine species of fish and invertebrates make up 99.5% of the reported high seas catch and are almost all destined for high-end markets. An assessment of 48 different high seas fish stocks showed that three-quarters are considered depleted or overfished. Industrial fisheries in the high seas have not only reduced the relative abundance and spatial range of target and non-target species, but have also possibly led to species imbalances and impacted the overall resilience of the ecosystem by reducing the abundance of certain functional groups and the overall species richness.

Since 1950, the United Nations (UN) Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has compiled and presented fisheries landings (weight estimates by taxa) by member states. The member state is the unit of decision making for addressing high seas fisheries management at the UN. The ‘‘nationalization’’ of fisheries was further emphasized after the 1982 United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which delineated exclusive economic zones (EEZs) and strengthened the ability of coastal and island nations to control fishing activity within 200 nautical miles from shore. Member states also exercise their political interests in the high seas through their engagement in 17 Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs)— the international governance bodies responsible for managing many transboundary fisheries, including most high seas fisheries. Although decision making formally falls to member states, corporate actors, including individual companies or industry associations, also partake in RFMO annual meetings, which provides them with a unique position to influence political and operational outcomes. Governments have also been the primary unit of assigning high seas fishing effort, with China, the fishing entity of Taiwan, Japan, Indonesia, Spain, and the Republic of Korea accounting for 77% of the identified global high seas fishing fleet and 80% of all high seas fishing effort for 2016. However, countries do not fish; when it comes to industrial fisheries, companies do. This is the first attempt to attribute high seas fishing effort to corporate actors.

Non-state actors, especially industrial producers, are under increased scrutiny for their responsibility for anthropogenic impacts. Previous studies showed that 84% of 228 companies involved in seafood production and traded on the stock market did not disclose what or where they are fishing. These analyses lacked details about the geography of the fishing industry. So, who is the high seas fishing industry?

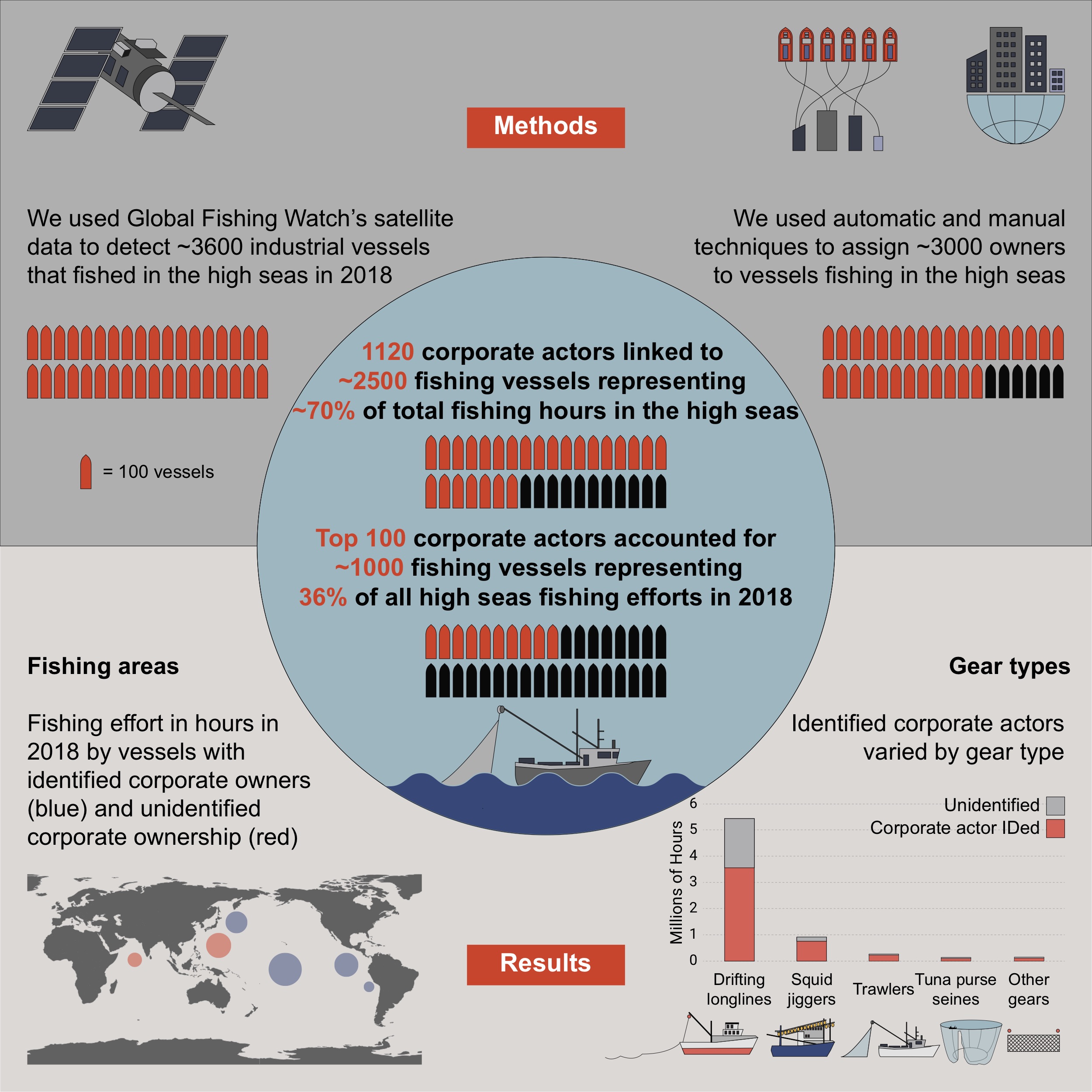

A study by Gabrielle Carmine and co-authors Juan Mayorga, Nathan A. Miller, Jaeyoon park, Patrick Haplin, Guillermo Ortuño Crespo, Henrik Österblom, Enric Sala, and Jennifer Jacquet set out to provide a first overview of the fishing industry in the high seas. Data was collected on the vessels that fished in the high seas during one year and subsequently developed a unique database of vessel owners (often individuals) as well as corporate actors (institutions) of each of these vessels as well as their hours of fishing effort. The research team collected data from Global Fishing Watch (GFW) and identified 3,584 unique fishing vessels finishing in the high seas in 2018. 3,051 of these unique fishing vessels (representing 90% of total effort) were assigned owners and 2,482 vessels (representing 69% of the total effort) were matched to 1,120 corporate actors (Figure 1).

Effort is color-coded and split into vessels with identified corporate owners (top; blue) and unidentified corporate ownership (bottom; red). Corporate actor ownership of fishing vessels are best identified in the Atlantic Ocean and the Western North Pacific, while the vessels with unknown corporate actors are concentrated in the Western Tropical Pacific. The dark gray areas along the coasts represent EEZs. Basemap is courtesy of ESRI.

The most readily available information came from corporate actors in the Atlantic Ocean and Western North Pacific Ocean, and the Western Tropical Pacific region provided the least information. Additionally, most corporate actors fishing in the high seas pocket encompassed by the EEZs of Micronesia, Papua New Guinea, Palau, and Indonesia were difficult to determine (Figure 1).

For high seas fishing vessels with identified corporate ownership, there was consolidation of fishing effort and corporate actors, and the top 100 corporate actors controlled 977 vessels and accounted for 36% of fishing effort in the high seas in 2018. Many of these corporate actors are global brands, with transnational supply chains, distribution, and subsidiaries. Sajo Group, headquartered in the Republic of Korea with subsidiaries around the world (including in the United States of America [USA] and Argentina), was the most active corporate actor, with 45 high seas fishing vessels (Table 1). The second most active corporate actor, China National Agricultural Development Group, is a state-owned company and the parent company for China National Fisheries Corporation (CNFC). Dongwon Group, the sixth most active corporation in the high seas and headquartered in the Republic of Korea, wholly owns the subsidiary Starkist Tuna, a prominent tuna brand in the USA. Six of the 10 largest corporate actors are headquartered in China, two in the Republic of Korea, one in Chinese Taipei, and one in the USA (Table 1). Of the 193 member states to the UN, 51 were headquarters to at least one of the 1,120 corporate actors identified. Of the 1,120 total corporate actors identified in this analysis, 103 corporate actors that owned 194 vessels (which accounted for 4.5% of the 2018 high seas fishing effort) were based in the USA.

In terms of the high seas fishing fleet, the average high seas fishing vessel spent 76% of its time fishing in the high seas and the vast majority of the fleet (78%) spent the majority of their time (>50%) in the high seas (Figure 2). While 91% of the 1,120 high seas corporate actors identified in this analysis fished both within and beyond national jurisdictional boundaries, the relative ratio of high seas fishing to fishing within EEZs varied (Figure 2). All of the top ten corporate actors linked to high seas fishing vessels spent the majority (62%–100%) of their total fishing activity in the high seas, and six of the ten companies spent more than 90% of their fishing hours in the high seas (Table 1). Three-quarters of the vessels for which researchers were unable to assign corporate actors spent 75% or more of their time in the high seas (Figure 2). In most cases, the vessel’s flag state was the same as the headquarter location of the corporate actor, with some exceptions. For approximately 6% of high seas fishing effort with an identified corporate actor, the corporation’s listed headquarter location was different from their vessel’s flag state.

Bars are color-coded; identified corporate owners (blue) and unidentified corporate owner (red). Many vessels without identified corporate owners spent all of their fishing effort in the high seas.

For high seas trawling (both mid-water and bottom), 96% of fishing effort was assigned to corporate actors. Bottom trawling, which cannot currently be distinguished from mid-water trawling from satellite data, is considered a particularly destructive form of fishing gear.

Showing fishing hours (2018) with identified corporate actors (also expressed as percentage of total fishing hours by gear type) and unidentified corporate actors. Category ‘‘other gears’’ includes pole and line, set longlines, pots and traps, set gillnets, and others.

This study is the first to assign high seas fishing effort to corporate actors, which revealed consolidation between corporate actors and effort in terms of the overall high seas fishing fleet, with the top 100 corporate actors representing 36% of high seas fishing effort. While 69% of the overall effort was linked to a corporation (Figures 1 and 2), gaps remain, particularly for drifting longliners, the most prevalent gear type in the high seas. It is important to note that there were undoubtably high seas fishing vessels missing from the GFW dataset due to not having (or not turning on) AIS transponders. Due to the lack of systemic transparency in the fishing industry, it is often difficult to determine the parent company or aspects of vessel identification. In this study, 40% of the studies vessels the listed corporate actor was not the ultimate parent company. Additionally, an estimated 20% of vessels fishing in the high seas are unequipped with AIS devices creating data gaps. Satellite data show that there is a set of fishing vessels that spend the vast majority of their time fishing in areas beyond national jurisdiction (Figure 2), and the methods developed for this analysis demonstrated the possibility to link corporate actors to observed high seas fishing vessels and effort. These methods can help compensate for the lack of publicly available data from certain companies, and the results of this analysis further emphasize the critical role of China for a sustainable ocean. There is promise in applying this approach to the entire global fishing industry, including fishing effort within national jurisdictions. Viewing attribution for high seas fishing through the lens of corporate actors, rather than through a flag-based framework, provides new ways to engage with the operational decision makers of high seas fisheries.

The high seas, its biodiversity, and its ecosystems are exposed to increasing levels of anthropogenic pressures and lack adequate protection and regulation due to weak governance with very little traceability and accountability. The availability of new satellite datasets of the high seas fishing fleet coupled with vessel owner information and corporate structures provides insight into the industry that profits from the global commons. Understanding which industry actors benefit from high seas fisheries can provide additional leverage for protecting the high seas—both through traditional forms of national and international control as well as through less conventional forms of social change that are urgently needed in the twenty-first century.

Read more about the corporate actors involved in high seas fishing here: https://www.cell.com/one-earth/fulltext/S2590-3322(20)30607-2

- Carmine et al., 2020, One Earth 3, 730–738, December 18, 2020, Published by Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2020.11.017

- Halpern, B.S., Walbridge, S., Selkoe, K.A., Kappel, C.V., Micheli, F., D’Agrosa, C., Bruno, J.F., Casey, K.S., Ebert, C., Fox, H.E., et al. (2008). A global map of human impact on marine ecosystems. Science 319, 948–952.

- Swartz, W., Sala, E., Tracey, S., Watson, R., and Pauly, D. (2010). The spatial expansion and ecological footprint of fisheries (1950 to present). PLoS ONE 5, e15143.

- Tickler, D., Meeuwig, J.J., Palomares, M.-L., Pauly, D., and Zeller, D (2018). Far from home: Distance patterns of global fishing fleets. Sci Adv 4, eaar3279.

- Schiller, L., Bailey, M., Jacquet, J., and Sala, E. (2018). High seas fisheries play a negligible role in addressing global food security. Sci Adv 4, eaat8351.

- Cullis-Suzuki, S., and Pauly, D. (2010). Failing the high seas: A global evaluation of regional fisheries management organizations. Marine Policy 34, 1036–1042.

- Cullis-Suzuki, S., and Pauly, D. (2016). Global Evaluation of High Seas Fishery Management. In Global Atlas of Marine Fisheries: A critical appraisal of catches and ecosystem impacts, D. Pauly and D. Zeller, eds. (Island Press), pp. 76–85.

- Ainley, D.G., and Pauly, D. (2014). Fishing down the food web of the Antarctic continental shelf and slope. Polar Rec. (Gr. Brit.) 50, 92–107.

- Ortuño Crespo, G., and Dunn, D.C. (2017). A review of the impacts of fisheries on open-ocean ecosystems. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 74, 2283–2297.

- Sala, E., Mayorga, J., Costello, C., Kroodsma, D., Palomares, M.L.D., Pauly, D., Sumaila, U.R., and Zeller, D. (2018). The economics of fishing the high seas. Sci Adv 4, eaat2504.

- McCauley, D.J., Woods, P., Sullivan, B., Bergman, B., Jablonicky, C., Roan, A., Hirshfield, M., Boerder, K., and Worm, B. (2016). MARINE GOVERNANCE. Ending hide and seek at sea. Science 351, 1148–1150.